Prologue

On August 20, 2000, my brother committed suicide. David Richard Huff was just over a month away from his 42nd birthday.

I have written about David almost every year since, usually around the anniversary of his death. Some years I make a minimal acknowledgement that it happened, a tweet, perhaps, including the number or web address for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Some years I write something in-depth.

This year, because suicide is so much in the news after the heartbreaking death of the gloriously gifted comedian and actor Robin Williams, a performer I’d loved ever since I first heard the word “Shazbot” in the late 70s, I feel like I can’t escape the subject. So here I am, again. I am tired of reading the things even the most well-meaning people have to say about mental illness and suicide. This is probably all I have to say about it, at the moment. This isn’t an admonishment, or an explanation. It’s just a story, and a ragged one.

You could read this as if it was a poem. But for this, poetry feels weak. You could read it as fiction. But it’s not.

A couple of years before David died, my father said, “You should talk to your brother. You’re more alike than you realize.”

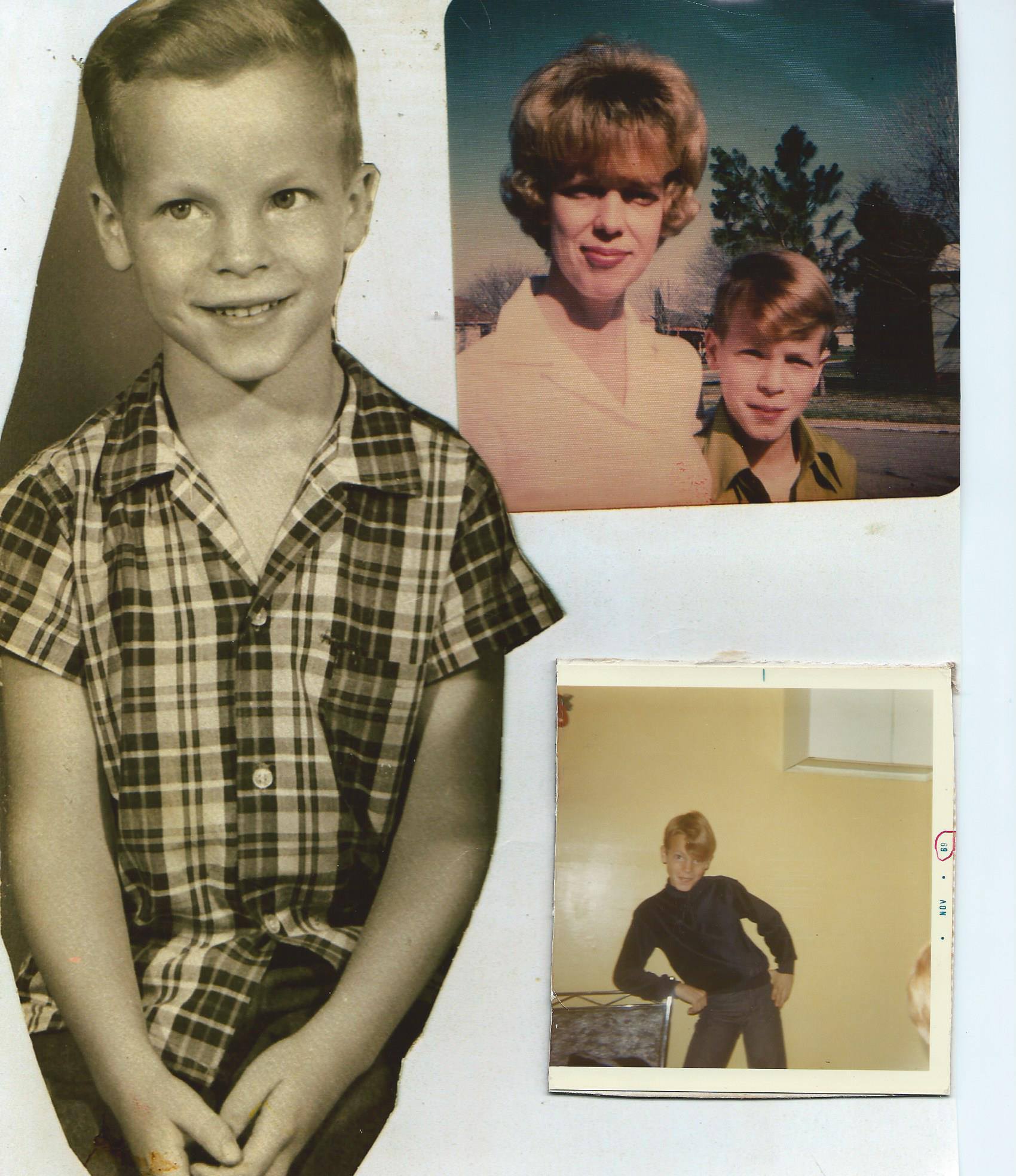

I probably sneered. We resembled, sure. Both 6’0″, both fair-haired, him blond and me a redhead. We had similar jawlines and noses. But David was trimmer, better-looking. He had an ease with women that was unnatural compared to my overly intense awkwardness. He could be incredibly funny and fun to be with, but he was also tough as nails, the kind of rough and ready fighting man other rough men tell admiring tales about, like one I recall of him taking on more than 2 or 3 other guys in a brawl outside a redneck bar. I was a writer and went to college to be an opera singer, for God’s sake. Aside from having the same parents, what did I truly have in common with my hard-living, rough-handed, truck-driving big brother?

I.

Memories of the days surrounding David’s death are patchy. Some moments are crystalline, far too clear for comfort even 14 years later. Others are blank, or veiled in grief’s gray and lingering haze.

There was the call to where I lived at the time, in rural middle Georgia. My sister Sherry, her voice ragged, calling early in the morning to tell what she knew.

A little later, I talked to my parents. They’d moved to a town in central Mexico where many Americans go to retire, because it’s temperate and beautiful and the locals are always friendly to the expats.

Mom was choked, but she could talk.

Dad just wailed. Across all those miles, his was the voice of a great wounded animal, terrible, trumpeting spasms of grief.

II.

He had always been a wild man but the first report of David’s madness was so florid and strange it took me years to really believe it happened. I was in college at the time, engaged to a surreal blonde girl whom I would later realize was far too smart and disturbed for me.

He had come home to Smyrna, Tennessee after a long-haul trucking run to Pennsylvania, convinced he was possessed with the spirit of a little boy from France. He’d spiraled further out of control once he reached the trailer he shared with his wife and young son on Almaville Road. At some point he threw things through the living room window. There was apparently a police standoff before they took him away.

At some point David made his wife and son dance to shake the demons out.

III.

I never lost track of reality. Sure, in my junior year of college I came down with food poisoning then convinced myself my girlfriend had tried to poison me. Sure, I stopped fulfilling all my obligations at one point because I convinced myself if I stayed home the world wouldn’t end. But I never hallucinated. I still knew I was Steve. I was nothing like my brother, with his ramblings, his ideas about demons.

IV.

David parked his truck at a rest stop in east Tennessee. He took off his clothes and ran around giving away his money. Again, the police came. They had a standoff while he held a Swiss Army Knife to his throat.

David thought the knife was a blessing. It bore the Cross of Jesus.

V.

I’d broken up with the surreal blonde girl. My new girlfriend and I would marry in the next couple of years. I was taking my first antidepressant, prescribed by a doctor who had cerebral palsy. He looked like Allen Ginsberg if the beat poet had been hatched from an alien chrysalis. He hugged me at the end of our last session and told me I’d climbed a mountain.

I was slated to sing the solo with our university choir in a grand and escalating spiritual that sketched the birth of the Christ child then traced his path to Easter. I entered the music hall dry and tired from the antidepressant, but the moment I began the solo, some animating spirit took hold. The audience stood and applauded for several minutes. I took several bows. Our director loved the response so much he encored the piece in the spring concert.

In the end I only drank too much that night, but I clearly recall going back to my apartment feeling that was a good high note. I could go out on that. I could kill myself.

VI.

The last time I saw my brother alive, I was afraid. He’d had more meltdowns and my parents said he’d long been compounding things with drugs. I’m still ashamed to say I awaited his arrival at the apartment I shared with my (first) wife with fear and hesitation. Our first baby had been born premature several months before and as David pulled up in his ramshackle car all I could think about was her.

Then he was in the door, and he was the old Dave, the brother I knew. His shoes were threadbare, and his false teeth ill-fitted, but he was funny and kind and unrelenting with big brotherly advice, even though I kind of knew much of what he tried to tell me already. As we sat on my apartment balcony talking at sundown, he spotted a pretty woman close to his age entering an apartment on the bottom floor. He said hello and smiled and her eyes crinkled and she smiled back.

I asked him if there was anything he needed. He asked for a clock radio and a coke. That was all. He was that specific.

And I realized, I told my mom later, that I would have given him almost anything he asked for then, if I’d had it. I had no explanation for feeling that way, save that he was my brother.

VII.

I left work that day to commit suicide. I’d realized I couldn’t take my life, my shattered marriage, just breathing anymore, and there was only one rational solution. I selected a bridge downtown. Along the way I passed the mental hospital near Nashville’s Centennial Park. I thought of my children and something my chrysalis Ginsberg doctor once said about what you should do if you want to hurt yourself.

Admit me or I’ll kill myself, I told the trim little man with the silly mustache who met me at the lobby desk.

He took me into a small room and questioned me about my state of mind.

His hands shook as he took my things for safekeeping, as the initial observation ward was more like jail than a hospital ward: keys, my wallet, a bottle of Prozac that had stopped working weeks ago, a notebook, a ridiculous packet of Vivarin.

I was admitted to the psych ward wearing jean shorts, a tee-shirt, sandals, and an empty fanny pack.

VIII.

Driving north from middle Georgia toward Nashville on the day David died, I saw off the side of the interstate a great natural sculpture built from kudzu vines and a telephone pole. It was a towering green reaper shimmering in a hot yellow haze. Great green summer Death, pointing north.

I pulled off the interstate and cried for what seemed a very long time.

IX.

I want this to be about real blood and the idea of blood, the thing that sings in our veins when we’re with family. How the song sometimes slips for a moment into a great column of harmony, flooding the listener with relief. Family as a hymn.

I want this to be a neatly-rendered essay suitable for framing or publishing elsewhere.

Instead, I can only recount cleaning David’s watch.

After his funeral, we divided up his meager things. Among them was a watch in a biohazard bag. It was a silver wind-up analog Timex with a flexible band. It was splattered with blood and other matter.

Once I was back in Georgia I put the biohazard bag in a roll-top caddy we kept at one end of the kitchen counter.

I don’t remember how long it sat there, but it wasn’t long. I know I often stared at it, imagining David buying it in a truck stop. Winding it. Slipping it off before bed.

One night I couldn’t sleep and I decided to clean the watch. Under the glare of that cookie cutter apartment kitchen’s track lights I put on dishwashing gloves and slipped David’s watch from the biohazard bag. I washed it under very hot water.

I remembered playing Go Fish with David, how the game would always devolve into “52-Card Pickup.”

I remembered getting him a “10-4 Good Buddy!” joke license plate for Christmas one year, a nod to his job, to his drawling and sarcastic persona on the CB radio, and overhearing him tell my mom he didn’t have the heart to tell me he’d never use it because “Good Buddy” was trucker slang for a gay man.

I remembered being 7 and riding with him on his motorcycle down the straightaway on Hamilton Church Road toward the sharp hairpin turn in the road where it once snaked into what was now a lake, how I screamed in joy and fear as he banked along the curve.

I washed David’s watch for several minutes, carefully inspecting each segment of the band as I went.

When I was satisfied it was clean, I set it to the proper time and put it on.

X.

Memory’s ostinato doesn’t constantly repeat the last time I saw my brother alive, even though I hold onto the low, waning light, the woman in the parking lot, his rattle-trap car and his shoes. It doesn’t cycle obsessively through those good childhood memories, or the times he was a typical big brother, teasing me, hassling, mocking.

When I turn over my brother and I in my mind, the memory that burns brightest is working beside him one summer when I was 15 and he was 24. We worked for our father’s company and the big job was installing runway lights at a small airfield south of Nashville. David enjoyed telling me what to do, but I felt like he was protecting me from the many strange and rough men on the crew, with their beards and Bowie knives and .357 Magnums tucked under driver’s seats.

One day a summer storm blew in from nowhere as David and I were finishing a ditch the crew had dug to find the old conduit carrying cables to the runway. There was pounding rain, jagged blasts of lightning. The other men on the crew figured they weren’t paid enough to work in the rain and dispersed, thinking (wrongly, I’m certain) my dad would understand.

My brother decided the ditch was too important to wait for the rain. You don’t have to, he told me, grabbing a shovel, but I’m going to keep it up.

In the steadily strengthening storm he hopped into the ditch and began digging wildly. In a moment I grabbed another shovel and joined him. We were alone on the job, at the bottom of a steadily flooding ditch, slinging wet red mud onto the scarred tarmac above. We only quit when the muck reached our knees.

That’s how it happened, that’s where it ended and we went on home, both soaked to our bones.

I keep re-imagining that day.

In my mind I keep breaking time’s chains to return to that ditch and the rising, rusty water. The broken slideshow reel in my head becomes a film of us flailing at the mud as the ditch floods. We are indistinguishable mud men, wielding flashing shovels against the storm’s onslaught.

We match each other, shovelful for shovelful, until the water takes us, and we drown.

Reblogged this on C.V. Madison and commented:

This is a really strong account of what it’s like to be on both sides of the fence in a kind of Schrodinger’s dance with depression and suicide. Very apt. TW: Suicide

Thank you for sharing this.

I also thank you for this. xo

That was beautifully written. And thank you for going into such personal depth to describe the things that can’t be explained.

I lost my best friend to suicide, and your essay reads just like my memories of him do – patchwork, worn, but still loved. Thank you for sharing your story of your brother, and I’m sorry for your loss.

Powerful. Personal. Incredibly poignant. Thank you.

So sorry for your loss, Steve. I fear for my own brother as well and struggle daily with what to do. What. To. Do. Thank you for sharing this.

I’m sorry. This piece is beautiful. I get it. ♥